Fall of the I-League : A tale of AIFF’s neglect and ISL’s monopoly

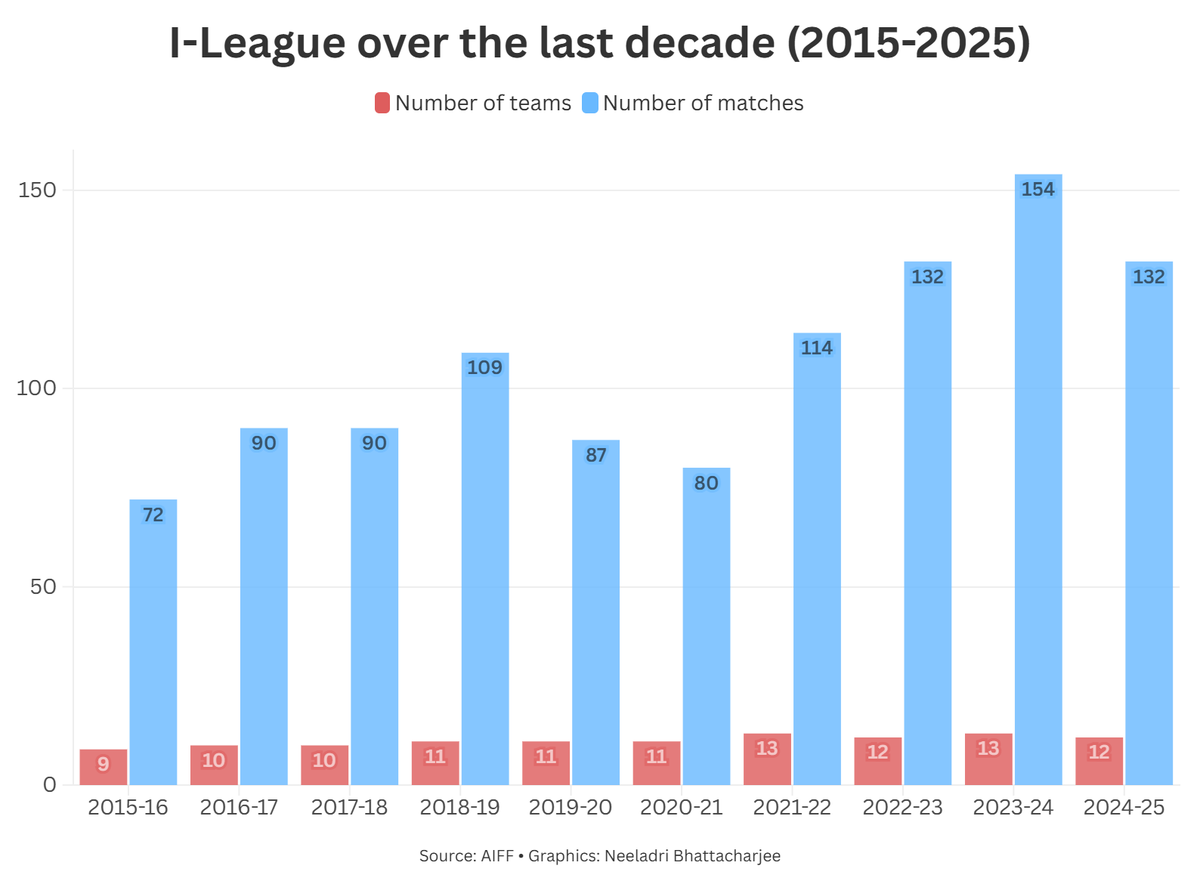

The I-League, which operated as the Indian top division for 12 years between 2007 and 2019, has delivered thrilling stories and nail-biting title races. Yet, year after year, its struggles have only been compounded. Meanwhile, the Indian Super League (ISL), initially launched as a franchise tournament in 2014, became Indian football’s top-flight in 2019.

Stripped of its top-tier status, coupled with poor scheduling, lack of marketing and insufficient broadcasting, the I-League has seen several clubs pushed into disarray. Since 2014, eight clubs from the league have shut down, including former champions Salgaocar FC and Chennai City FC. The I-League has borne the brunt of the All India Football Federation’s (AIFF’s) apathy towards its own competition.

MRA responsible for I-League misery

V. C. Praveen, the owner of Gokulam Kerala, points to the Master Rights Agreement (MRA) signed between the AIFF and Football Sports Development Limited (FSDL) in 2010 as the root cause of the second division’s predicament.

“From scheduling onwards, everything about Indian football is very poor now. The minute the MRA was signed, Indian football was killed,” says Praveen. “They were only safeguarding their interest. The AIFF was very comfortable with the marketing money they were receiving, so they became very lazy.”

In 2016, three Goan clubs — Dempo SC, Salgaocar FC and Sporting Clube de Goa — withdrew from the I-League, opposing the move to make the ISL the premier division. The Asian Football Confederation (AFC), in its roadmap with the AIFF, designated the ISL as the sole first division in 2019.

Promotion from the I-League to the ISL was introduced in 2023, with Punjab FC and Mohammedan SC earning ISL spots in the next two seasons. The uncertainty around promotion between 2019 and 2023 financially impacted I-League clubs

“That was the crux of the financial distress we had,” says Rohit Ramesh, owner of Chennai City, which won the league in 2019. “If you won the I-League, there was still no guarantee that you would play in the ISL. That was the beginning of the end.”

The new MRA draft from FSDL also shuts the door on I-League promotion for the next five years, ‘unless explicitly voted for by all stakeholders’.

“What is wrong with promotion and relegation?” asks Praveen. “Indian football is divided into rich and poor, and they don’t want the poor to come into the rich man’s league. Just because one club fails to meet the demand, they shouldn’t say promotion and relegation are difficult or uncomfortable.”

“Investors put money into clubs mostly because they see an opportunity to get into the ISL. That has helped the I-League to survive,” adds Anuj Gupta, co-founder of former I-League side Sudeva Delhi Football Club, which currently plays in I-League 2. If that stops, the league could shut down because there is no motivation.”

Financial struggles aplenty

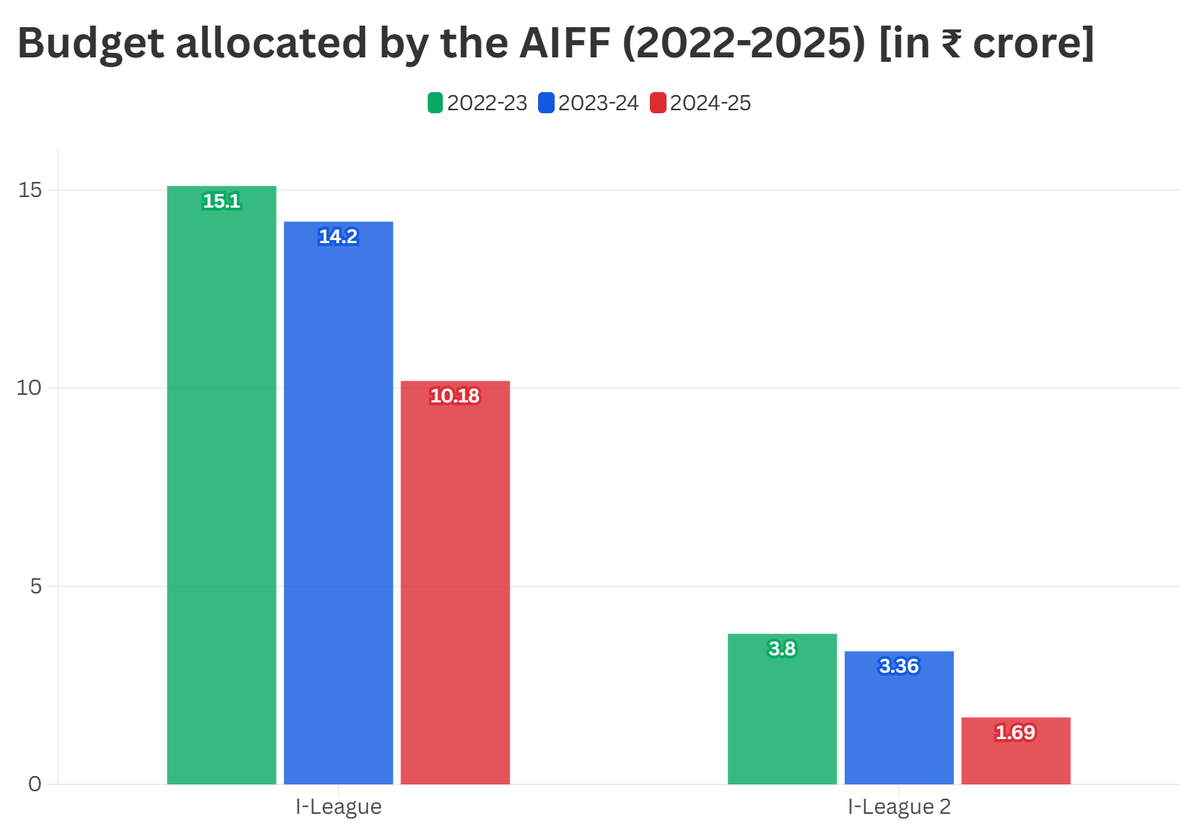

The AIFF’s budget allocated for the I-League has kept falling over the years — from ₹15.1 crore in 2021 to ₹10.18 crore last year, marking a 33 per cent drop. Moreover, in 2022, the cost of broadcasting was deducted from the clubs without informing them in advance.

Pall of gloom: Chennai City FC is one of the eight I-League clubs to have shut down since 2014.

| Photo Credit:

NISSAR AHMAD

Pall of gloom: Chennai City FC is one of the eight I-League clubs to have shut down since 2014.

| Photo Credit:

NISSAR AHMAD

“The production cost in the very first year (under President Kalyan Chaubey) was ₹2 crore. And that money — around ₹17 lakh per club — was taken from their subsidies without even asking them,” says Ranjit Bajaj, owner of I-League side Delhi FC, to Sportstar.

Clubs receive around ₹50–55 lakh in subsidies, and this deduction hit their finances significantly, by at least 30 per cent.

Last season, with less than two weeks to go before kick-off, clubs managed to bring Sony Sports on board as the television broadcaster, paying ₹2 crore from their own pockets.

“Earlier, the I-League was telecast on Star Sports. Then they said no one was watching it — so how did we get Sony? So, the I-League club owners showed initiative and managed to get all matches broadcast on Sony TV,” says Praveen.

Last month, all I-League clubs wrote to the AIFF requesting a reduction in Club Licensing fines so they can survive in the long run.

“These fines, as we have raised in multiple individual and joint discussions with you, are excessive and, in many cases, unjust, given the financial and operational constraints under which I-League clubs operate,” read the letter.

Sportstar understands that I-League clubs were fined around ₹2 crore for licensing breaches.

“I feel the biggest losers have been the club owners. At the end of the day, they’re spending from their own pockets but not getting even the same returns they did four years ago,” Anuj adds.

Issues down the order

Further down the structural pyramid, in I-League 2, similar challenges persist. The AIFF’s budget allocation for the league has fallen by over 55 per cent in just three years.

“Limited visibility, inconsistent refereeing standards, infrastructure gaps, and constrained revenue opportunities are all significant hurdles,” says Gaurav Manchanda, owner of I-League 2 side FC Bengaluru United (FCBU), established in 2018.

Anuj added that the lack of sponsors and prize money makes the league an uphill battle.

“Last year, we played I-League 2 in a home-and-away format. So, the logistics cost was at least ₹40 to ₹50 lakh,” he says. “But we hardly received any money from it. If you finish in the top four of the I-League, you get some prize money. We finished third in I-League 2 last season, but got nothing.”

Yet, there are positives to the league. Over the past two seasons, 57 clubs across 23 states have participated in the I-League, I-League 2 and I-League 3, making it a truly pan-India competition.

“The good thing about I-League 2 is that no foreigners are allowed,” says Anuj, while Manchanda adds, “The shift from the traditional group stage format to the current qualifier league format has brought much-needed stability and consistency to I-League 2.”

Clubs now get a guaranteed 14 games over two to four months, which improves squad planning, financial security, and makes the league more meaningful.

The Indian football pyramid is in disarray, starting from the top-flight. But if the layers below continue to erode, will the topsoil really remain? The AIFF will need to put a lot of thought into that before it’s too late.