Landing on the red planet

Up, up, and away!

The question of whether Mars supports life, or if it has in any point of its history, has been on the minds of people – both scientists and common folk – for a very long time. Flyby explorations of the red planet in the 1960s ended hopes of an inhabited world. In 1971, the Mariner 9 mission entered orbit around Mars and the photographs it returned showed surface features that could have been generated by liquids that had flown.

In such circumstances, the logical next step in Mars exploration was to place landers on the surface, with the necessary technology to analyse Martian soil and atmosphere. Budget constraints, however, meant that the concept of a single, long-duration Mars lander had to be revised and replaced with two orbiters and two landers with a shorter planned surface observation time.

The result was the two-part Viking mission, with both Viking 1 and Viking 2 having an orbiter and lander. Using smaller launch vehicles and scaled-down mission objectives, the mission aimed at investigating Mars for signs of life with a targeted minimum of 90 days on the planet.

The Titan III-Centaur carrying the Viking 1 lander lifted off on August 20, 1975. The Viking lander conducted a detailed scientific investigation of the planet Mars.

| Photo Credit:

NASA

The Viking project was managed by NASA’s Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia. While the orbiters of the twin spacecraft were based on the Mariner 9 spacecraft and built by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California, the lander was built by Martin Marietta under contract to NASA Langley with JPL in charge of handling operations.

On August 20, 1975, Viking 1 was launched from Cape Canaveral, Florida. Even as it was making its way on its 304-day voyage to Mars, its twin, Viking 2, was launched on September 9 to begin its 320-day journey.

From one anniversary to another

On June 19, 1976, Viking 1 was in the vicinity of our neighbouring planet, entering into an elliptical orbit around Mars. The mission planners had grand ideas, planning for the Viking 1 lander to reach the Martian surface on July 4. This was special because it would have meant that the landing would coincide with the bicentennial of the U.S. – the 200th anniversary of the nation’s founding.

Even the best laid plans, however, might not fruition. Photographs that Viking 1 sent from its orbit showed the landing site that had originally been chosen for July 4 was rougher than expected. As celebrations made way for safety, another two weeks were needed to search and finalise a new, safer touchdown site for landing.

Viking 1’s orbit was adjusted and on July 20, the lander separated from the orbiter and began its descent towards the Martian surface. Once the soft landing in the Chryse Planitia region of Mars was successful, it almost immediately started beaming back photographs of its landing site.

Even though the bicentennial celebrations in Mars had been missed out, Viking 1 lander had made it to the Martian surface on another anniversary – one that is now equally revered, even throughout the world. For it was on July 20, 1969 that the Apollo 11 mission had achieved its grand success, allowing human beings to set foot on the moon for the first time ever.

Viking 2, meanwhile, entered into orbit around the red planet on July 25, with its lander successfully landing on the surface in Utopia Planitia on September 3.

The letter “B” or perhaps the figure “8” appears to have been etched into the Mars rock at the left edge of this picture taken on July 21, 1976 by the Viking 1 lander. It is believed to be an illusion caused by weathering processes and the angle of the sun as it illuminated the scene for the spacecraft camera. The object at lower left is the housing containing the surface sampler scoop.

| Photo Credit:

THE HINDU ARCHIVES

Picture perfect

The lander, which weighed 978 kg and looked in a way like a much bigger version of the Surveyor lunar lander, began relaying back information from the time it separated from the orbiter. This meant that even during the complicated atmospheric entry sequence, Viking 1 lander was taking air samples.

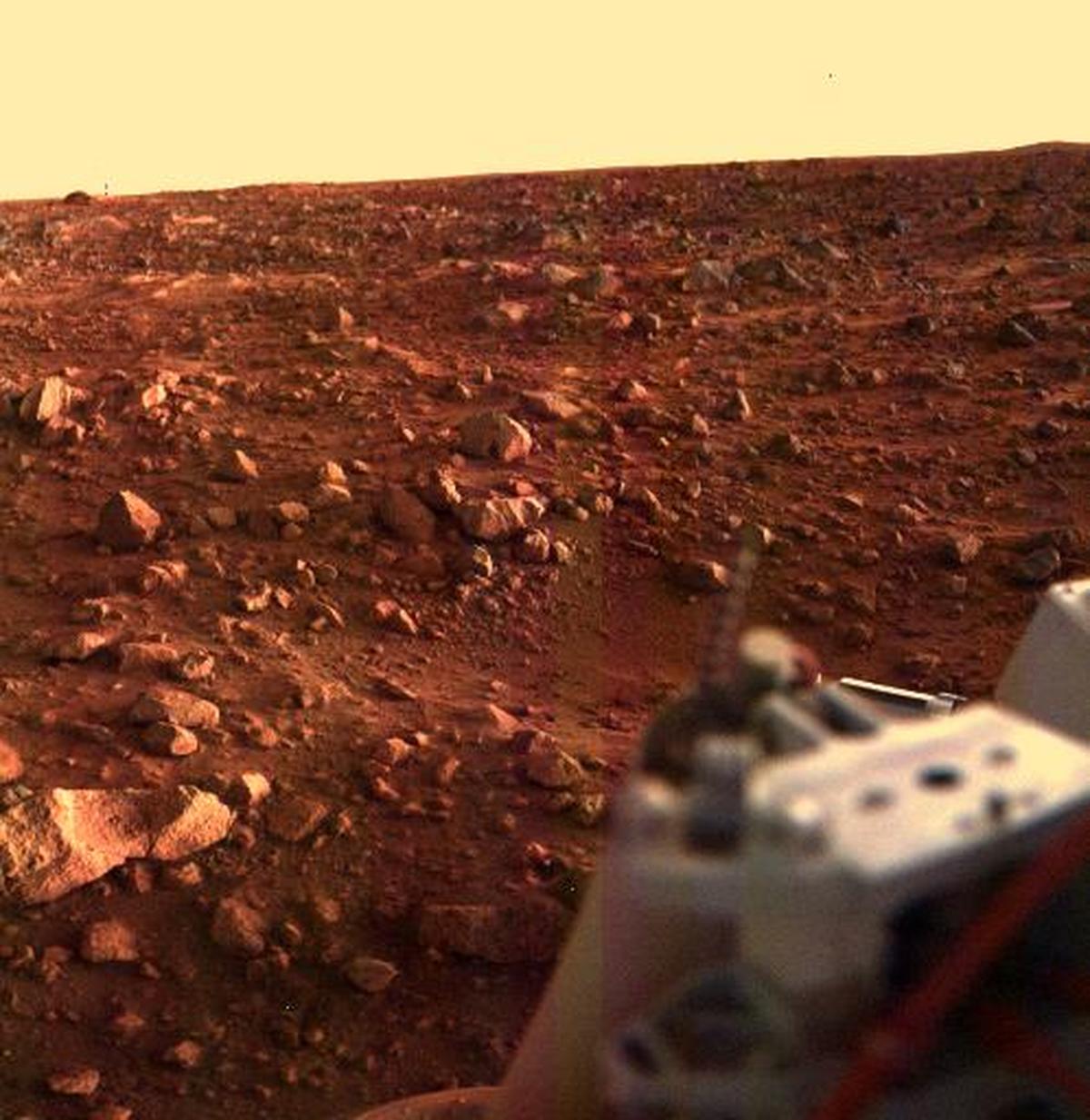

Once landed, the spacecraft took in its surroundings. In addition to high-quality, high-resolution images, the lander also managed panoramic views. While the 300-degree panorama of the lander’s surroundings showed parts of the spacecraft too, what mattered more was the rolling plains of the Martian environment.

Though pictures were high on the agenda, the lander did several other things as well. The seismometer might have failed, but the other instruments and equipment provided valuable data.

Instruments recorded temperatures on the Martian surface and these ranged from minus 86 degrees Celsius before dawn to minus 33 degrees Celsius in the afternoon. A little over a week after landing, Viking 1’s robot arm scooped up the first soil samples on July 28 and this was deposited into a special biological laboratory.

Data from Viking 1 indicated that there were no traces of life, but it did enhance our understanding of the planet’s surface and atmosphere. It helped characterise Mars as a cold planet with volcanic soil and an abundance of sulphur, different from any known material found on the Earth and its moon. The Martian atmosphere was shown to be thin, dry and cold, and primarily composed of carbon dioxide. Evidence for ancient river beds and vast flooding were also gathered.

First colour image from Viking 1’s lander.

| Photo Credit:

NASA/JPL

Outdoing expectations

The primary mission for both Viking 1 and Viking 2 ended in November 1976. Activities, however, continued well beyond that as both orbiters and landers exceeded their planned 90-day lifetimes by a distance. While Viking 1 and 2 orbiters continued their missions until August 17, 1980, and July 24, 1978, respectively, the landers observed weather changes on the surface until November 11, 1982, and April 12, 1980, respectively.

The Viking 1 lander first started sending out daily weather reports as part of the Viking Monitor Mission, which was eventually replaced to be a weekly report. Following the death of Thomas A. Mutch, who led the imaging team for the Viking project, on October 6, 1980, the Viking 1 lander and the site where it remains were renamed the Thomas Mutch Memorial Station.

The Viking 1 lander operated faultlessly until November 11, 1982, when a human error brought about its end. A faulty command sent from Earth interrupted communications with the lander, and further attempts to resume contact were of no avail. The landers of Viking 1 and 2 together returned 4,500 images from the two landing sites.

Sunset at the Viking 1 lander’s site.

| Photo Credit:

NASA/JPL

Having been on the Martian surface for 2,307 Earth days or 2,245 Martian sols, Viking 1 lander set the record for the longest operating spacecraft on the surface of Mars. Viking 1 held this record until May 19, 2010, when the Opportunity rover finally broke the record. Opportunity set that record at 14.5 Earth years or 5,111 sols, with its mission ending only during a planet-wide dust storm in 2018.