EXCLUSIVE — David Gower: World Test Championship is inevitably flawed

[ad_1]

Former England captain David Gower isn’t against Bazball — but he believes Test cricket’s future hinges on something bigger than England’s approach. One of England’s most elegant batters, Gower scored 8,231 runs in 117 Tests at an average of 44.25, with 18 centuries to his name — and he’s now calling for the ICC to urgently rethink how it supports its ‘relatively poor’ member nations if the longest format is to survive.

Speaking to Sportstar on the final day of the third Test at Lord’s, Gower weighed in on the ‘inevitably flawed’ World Test Championship, praised Shubman Gill’s early captaincy, and argued that for England, the challenge isn’t to abandon Bazball — but to know when to rein it in.

With aggressive batting and quick results becoming the norm in Tests, how do you view this shift — and do you worry about its impact on batting craft?

The idea of batting positively isn’t new. Back in 1985, during the Ashes here, we scored at over four an over in five of six Tests — which, for that time, was rapid. The Australians of the ’90s did it too: they’d score quickly to give (Glenn) McGrath and (Shane) Warne time to bowl teams out — and still fit in a round of golf. So, the concept has always existed. What England have done under (Ben) Stokes and (Brendon) McCullum is take it to new heights. The (Jonny) Bairstows, the (Zak) Crawleys, and others who love their shots have recorded scoring rates that are the highest in the last three to four years. And on its day, it’s thrilling to watch.

There’s huge entertainment value in it, but also a slightly desperate need to prove that Test cricket can still be entertaining. We’re talking on the fifth morning of this Test, and the buzz is absolutely electric. It was the same last night. This entire series has had moments that have reminded everyone what five-day cricket can offer.

For those lucky enough to be at the ground, it’s a real event — something you feel. That isn’t something you get with formats where you pop in for a couple of hours and leave with a result. I still believe Test cricket is the highest form of the game by some distance.

When Virat Kohli says it is, that’s great PR — because 1.4 billion people hear him. But we need more people speaking up for it. What we — my generation especially — always wanted from England was a blend of flair and grit. In the Lord’s Ashes Test two years ago, they collapsed in an hour of madness; only Stokes stuck it out. Since then, a few others have started to ride out the tough periods, then push on again with clear skies and fair winds. That’s progress. Over the past four years, there were moments when a different approach for an hour or two might have changed the result. And now, in this series, you can see they’ve begun to learn from those.

The pace of the Lord’s Test has been different. Batting hasn’t been easy — there’ve been no soft 200s. That’s fabulous. And you can feel it everywhere — the stands, the press box, the corporate boxes — this sense that you’re watching something special.

(Smiles) I wasn’t planning to come in today [final day]. But after last night, it felt like it would be a shame to miss it.

Is Bazball the way forward — or just a necessary tactic to keep Test cricket relevant in the T20 era?

If teams are capable of playing that way, then yes — it’s important for Test cricket to prove it’s still worth watching. In an era where white-ball formats dominate and data tells us fans love the instant thrill — balls flying to the boundary, sixes every few minutes — anything that shows how vibrant the long format can be is valid.

But not every team has the talent or depth to play that way. If you’re lower down the pecking order, you’ve got to find the best way you can to win a Test — even if that means playing more conservatively.

Look at Australia. Sure, they have someone like Travis Head, who fits naturally into a more aggressive mould. But their overall approach has often been pragmatic. That alleged culture clash in the Ashes two years ago — England’s ultra-positive style versus Australia’s discipline — ended with the pragmatic side winning.

Ultimately, in iconic series like the Ashes or the Border-Gavaskar Trophy, or even the World Test Championship final, it’s not about style points — it’s about doing what it takes to win.

And part of keeping Test cricket relevant is showing people that drama can unfold in many ways. In that WTC final, the ball dominated for two days — low scores, not your usual white-ball fare — and then Aiden Markram played a stunning innings to snatch the game. That ebb and flow, those wild momentum shifts, are unique to this format.

I know it’s a harder sell to younger fans — and nearly impossible to explain to Americans — but for those who still value Test cricket as the game’s highest form, their voice still matters, even if it’s a smaller group now.

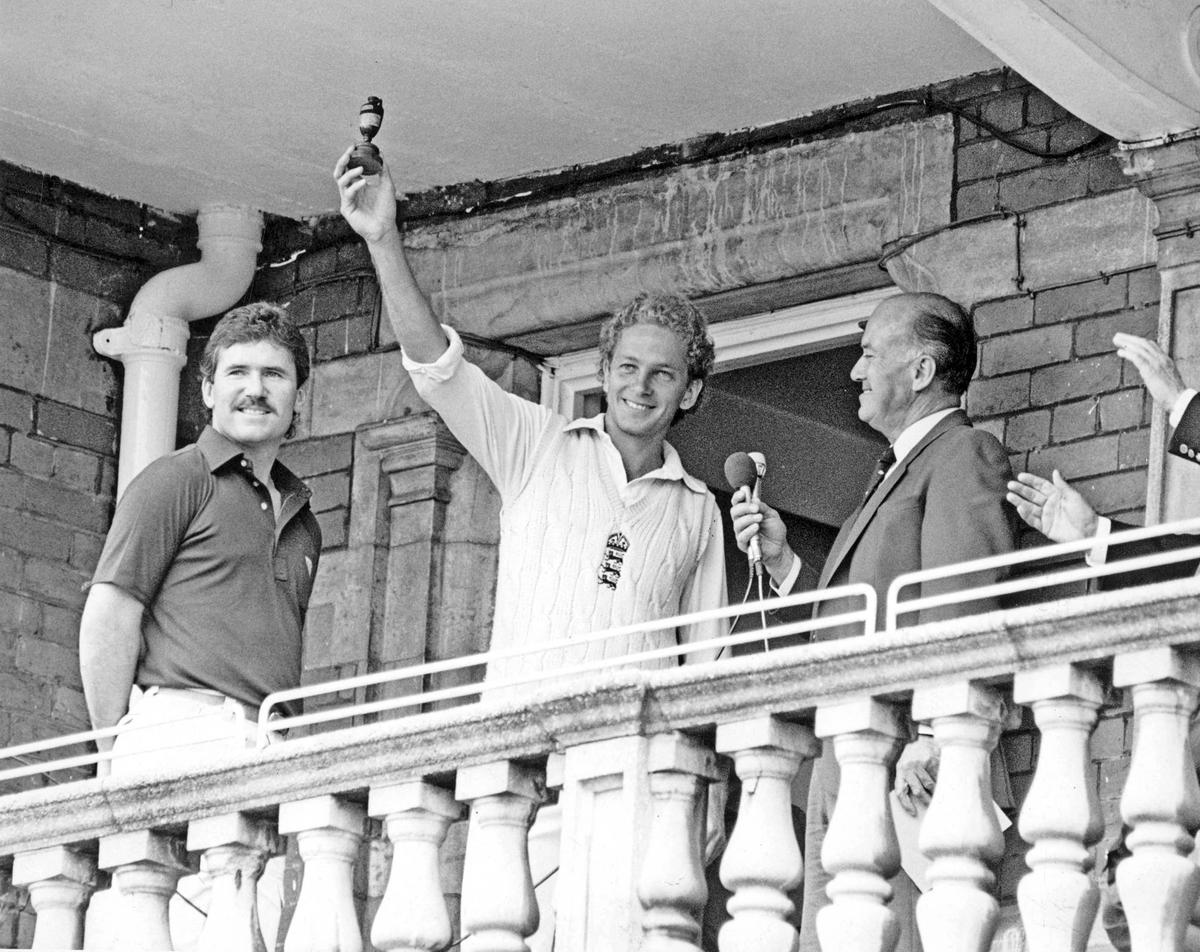

Ashes reverie: David Gower, England’s debonair captain, stands tall on the Oval balcony, cradling the Ashes urn — the gleaming symbol of a summer triumph. The 3-1 series win in 1985 is his crowning moment. Beside him, Allan Border embodies the stoic dignity of defeat.

| Photo Credit:

THE HINDU ARCHIVES

Ashes reverie: David Gower, England’s debonair captain, stands tall on the Oval balcony, cradling the Ashes urn — the gleaming symbol of a summer triumph. The 3-1 series win in 1985 is his crowning moment. Beside him, Allan Border embodies the stoic dignity of defeat.

| Photo Credit:

THE HINDU ARCHIVES

With T20 leagues on the rise and bilateral interest fading, what reforms can help safeguard Test cricket without ignoring the game’s commercial realities?

Well, I never quite know the answer to that sort of question. But what’s telling is how the conversation has shifted. Two years ago, influential voices were busy carving out windows for franchise cricket. Now, those same people are saying we need a dedicated window for Test cricket.

And it’s complicated, isn’t it? There are so many factors — money, resources, infrastructure. Lord’s is an exception: 28,000 people will turn up on a Monday for Day Five of a Test if the match is set up well. India still gets good crowds, though in a 100,000-seater, 30,000 can look sparse. Australia gets healthy numbers when we tour. But in the West Indies, the stands are nearly empty. Test matches there often lose money.

In New Zealand, they’ve at least adapted by using smaller grounds to make things feel fuller. But for many boards, the arithmetic doesn’t work. You can understand why a board like Cricket West Indies, already under pressure, might prefer eight days of white-ball cricket over 15 days of loss-making Tests. That’s a hard call to argue with.

So, unless the ICC can think of — I know it wouldn’t go down well in India — redistributing the funds that can help out the poorer nations, we will see Test cricket declining apart from the top three, four, five nations. (This can’t be) just an odd boost every other year or in three or four years, but year by year. So I’m not the Solomon who can tell you exactly how to solve this. But one of the things I do think very strongly is that if you want Test-playing nations to still be in business, then they need help.

With Bazball’s rise, England’s pitches seem flatter and more batting-friendly than before. Is old-school English cricket losing its edge?

(Smiles) I suppose these flat pitches suit Stokes’ desire to chase — well, sometimes.

Even this England team would agree that a better contest between bat and ball makes for a better spectacle. That’s been a mantra for so many of us over the years. Watching teams pile up 600 on certain flat pitches — it gets quite dull, doesn’t it?

Then there’s the commercial side to consider. Take this Lord’s Test: if it finishes in three days, that’s potentially two days of lost revenue. But how do you weigh that against the quality of entertainment the crowd has already had?

The dream is a fair contest, something in it for both batters and bowlers.

A game that lasts at least four days, stays tight, and builds toward a tense finish, like this one. That’s when Test cricket is at its best.

When Tests wrap up in just two or three days — especially in the subcontinent — does it hurt the format’s appeal?

Home advantage can be abused, of course. And when the temptation is to win at almost any cost, teams sometimes go too far. That series in India last year, for example — dominated by turning tracks — you could tell it wouldn’t last five days. And you could probably guess the result going in. But if you’re trying to reach the World Test Championship final, you want points and wins — that’s the reality.

England’s tour of Pakistan last October showed both extremes. One Test was on a flat pitch — Harry Brook’s triple hundred was brilliant in its own way. Then the next games, the ball spun, and we watched a side that was dominant unravel.

So yes, pitch preparation can shape a series — that’s undeniable. Whether that’s right or wrong is open to debate. Some dream of a unified pitch formula: ‘no, no, no, no, no, no. It’s only seam, flat and spin’ — as if there’s a dial you can turn remotely. That would be ideal. But let’s be realistic — you take what you get and try to win on it.

David Gower: “As a captain, you can just try and find a way of motivating or inspiring every man to be at his best somehow. That’s all you can do.”

| Photo Credit:

PTI

David Gower: “As a captain, you can just try and find a way of motivating or inspiring every man to be at his best somehow. That’s all you can do.”

| Photo Credit:

PTI

The WTC has added context to Tests — but what changes would make the format more relevant and engaging?

The World Test Championship is inevitably flawed — whether it’s the percentage system or the points lost for slow over-rates. It’s a brave attempt to address the issue, but clearly not enough.

The real problem is that it’s not an even contest. Not all top sides play each other, and everything depends on where, how, and who you play. No amount of maths can fix that imbalance.

That said, it does add context — especially for the teams in the top four pushing for a final spot. But if you’re sitting at number nine, frankly, no one gives a flying fox what happens.

India is in a rebuilding phase under a new captain. If you had a word with Shubman Gill, what advice would you give him on bringing the best out of his players?

Building a team depends on so many things. At the start of the series, people focused on the absence of Rohit (Sharma) and Virat (Kohli). But Shubman stepped up and played beautifully in two Tests.

You don’t have to be 34 to lead — you can be 24, if you’ve got talent, a good head, and a solid technique. That kind of player can fill the gap. If you’re one or two players short of a great side, you work around it and trust others to develop.

I trust my old colleague Michael Atherton when he says India won nine of the 10 days. That’s not bad for a team supposedly in transition. In Birmingham, they bowled better than us. At Lord’s, England finally found something in the ball we hadn’t really seen before.

Team-building often comes down to individual moments. Look at Stokes at Lord’s — this is the Stokes we’ve missed: bowling 90 miles an hour, driving the attack forward. You want all your key players at peak performance — that’s what shifts a match.

I always say, if six of your XI are playing to their potential, you’re in a good position. If six are having a shocker, you’re likely coming second. If all 11 hit their peak — you’re unbeatable. But that rarely happens. As a captain, you can just try and find a way of motivating or inspiring every man to be at his best somehow. That’s all you can do.

[ad_2]

Source link