Thomas Rohler Interview: Competing in India was on bucketlist, getting invited by Neeraj Chopra an honour

Two Olympic champions will be on the field at the Neeraj Chopra Classic in Bangalore on July 12. One, of course, is Neeraj Chopra himself, who lends his name to the tournament. The other is Thomas Rohler who won gold at the 2016 Games in Rio. Rohler was one of the men to beat during the 2016-2020 Olympic cycle – his 93.90m throw at the 2017 Doha Diamond League placed him third on the all-time list for the javelin throw.

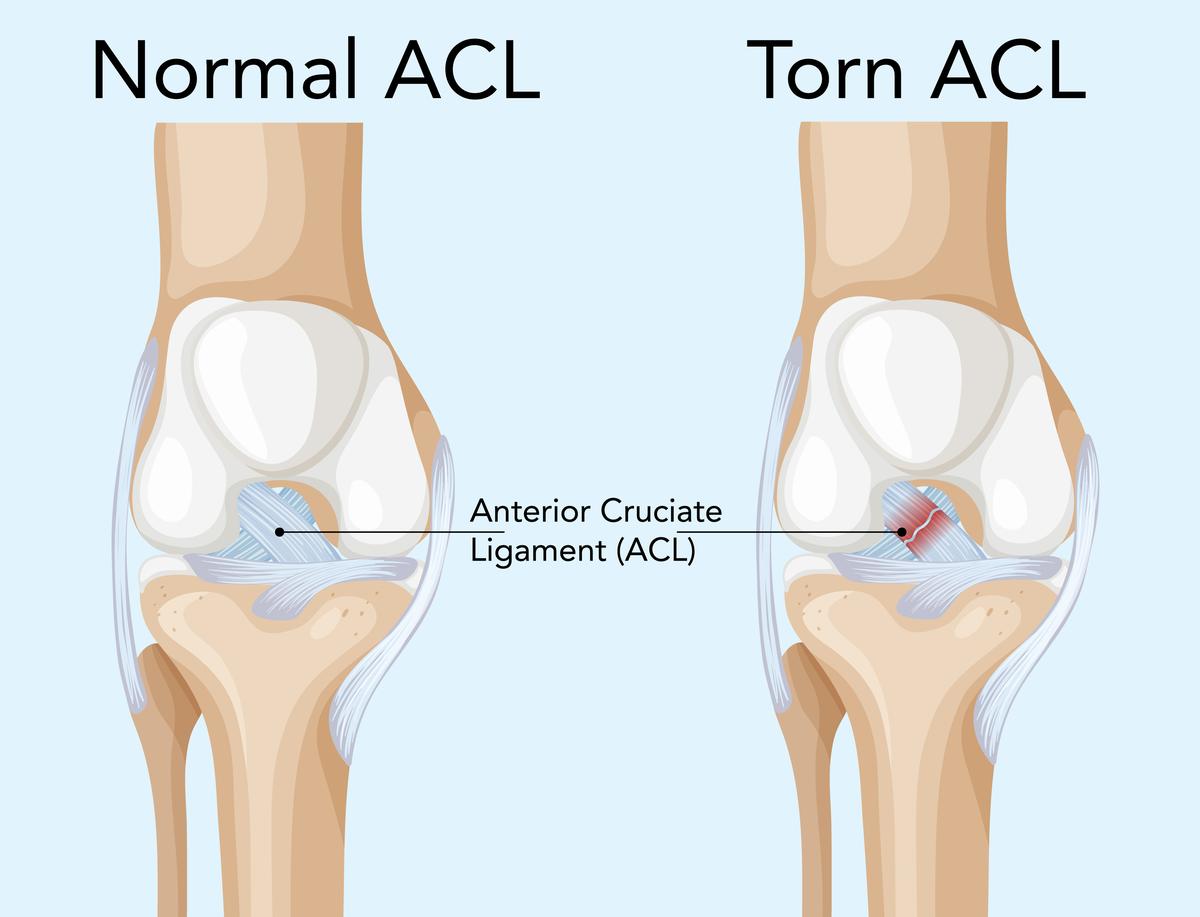

He would have been one of the favourites to defend his Olympic crown in Tokyo but for a serious back injury, following which Neeraj entered the history books himself.

Rohler’s comeback has been slow. He has struggled to find the form that made him a world-beater, eventually missing the 2024 Olympics as well. However, the now 32-year-old isn’t done with the sport just yet. In this interview with Sportstar, Rohler spoke about making peace with his injuries, what keeps him motivated, and what goals remain for an athlete who has already won nearly everything there was to win. He also spoke about the role Neeraj played in growing the sport and what explains the burst of talent in India in a discipline once dominated by European athletes.

Listen to the full chat on Sportstar Podcast

ALSO READ | Neeraj Chopra reclaims top spot in World Rankings, Arshad Nadeem fourth

Why did you decide to come to India?

Well, to be honest, it was really Neeraj who reached out to me, both directly and also via his management. So I decided to be there because competing in India was on my bucket list. I mean, it’s the fastest-growing javelin community in the world right now, and it’s just logical to have an international meet there. Getting the invite directly from the Indian Olympic champion was an honour. I was happy to hear that he’s super involved. I know from my own experience that conducting a meet is an extra bit of work for an athlete. I’m glad he is putting in the work to help the javelin community, so I’m happy to come and help him as well.

Neeraj was a big fan of yours back in 2016 when he was still starting out. What is it like to now compete at a tournament alongside him?

We have interacted and competed before. We are genuinely respectful to each other as athletes, but I also think we share the same Olympic values. This is something that has always connected us. This is how sport works — you start competing with your role models. I know it from my own experience: when I first started competing with (Andreas) Thorkildsen or Tero Pitkamaki, that was a huge moment for me. So I can feel how he must have felt competing for the first time against — or with — me. And this is just how sport evolves: the young ones come up and eventually start to beat you. That’s just how it goes. And it’s a good thing that it is that way.

What are your goals for the 2025 season?

I was struggling with a major back injury in 2020 that took quite a long time to recover from. Last year I tried to get back to competitions, which was not amazing, but OK considering where I was coming from. And now I’ve had a really, really good winter. Unfortunately, during fall, there was another break due to a Lyme infection, which really put me down. But honestly, since January, I’ve been healthy and training really well. I’m just looking forward to competing again. Training is one thing, and competing is another, and I’m just glad to be back on track soon.

I’m taking the long route back to where I was. I’m eyeing the World Championships a little. I have strong competitors in my own country — that’s good for Germany and for the sport, but at the same time, it’s a challenge for me. But more important to me is a steady season, to compete in at least eight to ten meets and get back to stable distances above 80 metres. Then I can take the next steps towards 2028.

What would you be satisfied with in Bangalore? What would you be satisfied with at the end of this year?

I’d be satisfied with a good-quality throw and a run-up that works. Over the last ten years of doing this, I’ve never set a distance as a target before any meet I compete in, and I’m not going to change that in 2025 either. I just want to maintain good quality in terms of training and competition. I want to see myself doing in competition what I’m currently capable of in training. Then I can move on into the season.

You have won the Olympic title, the World title, and have the third-best throw of all time. Are there any goals left for you?

I actually started thinking about this question after I won my Olympic gold in 2016. Before the 2016 Olympics, I had told the German media that one day I wanted to throw over 90 metres and that I wanted to compete at the Olympics. I’d never really thought about winning gold. I just wanted to be an Olympian. That was what actually drove me into sport. This is what gives me goosebumps when I look back at my career.

And then came all these cherries on the cake. What I found out is that what makes me super happy is the lifestyle, and also that I love leaving footprints. And the way I’m able to leave these footprints — not just for the next generation of athletes but also, in a way, for myself — is by being active in the sport.

So I want to stay healthy and I want to be associated with the sport. If I can win another big thing, that’s just amazing. But there is no ‘have to’ about it anymore. I just want to enjoy the sport and be there.

You almost never made it to the Olympic final in 2016 — you qualified for the final only on your last throw in qualification. Could you take us through your Olympic experience?

2016 was one of the most challenging seasons of my whole career. Something most people don’t know is that I injured myself really seriously at the European Championships in Amsterdam just a few weeks before the Olympics. I tore my latissimus (back) muscle, which is one of the bigger muscle groups. I was badly bruised all over my right side, and when I showed up for the MRI, they asked if I’d been in a motorcycle accident. I had to tell them I got it just by throwing a javelin.

Those six and a half weeks between that injury and the Olympics were among the most challenging phases of my career. I did know that I was throwing well and had the best throw of the season (91.28m at the Paavo Nurmi Games in Turku). At least on paper and according to the data, I was ready to go for a medal in Rio. But because of the condition of my body, I knew it was going to be difficult.

That qualification was actually a proving ground for me — whether I was ready enough to attack hard. I was really testing myself in the Olympic qualifier. I’m never a particularly good qualifier. I think many top athletes are like that—weak qualifiers and great final performers.

That’s what I’ve found, talking to all of these javelin champions and long jumpers, high jumpers, whatever, over time, because we spare the most power and the mind. That’s way more important for it. Like, we save our focus for when it really matters. So qualifying can be a little tough for us.

Over the years, I’ve started using qualifications to test javelins, my run-up angles, and see if I’m feeling good. So even though I qualified only at the end, I was never super nervous in the Rio qualifications. But I understand that I gave people back home — and my fans — a really hard time.

In fact, you weren’t even in the gold medal position in the final before your last throw. Were you nervous before that sixth throw?

I wasn’t looking at the other throwers in the final. I was just focusing on my individual control. I was going from throw to throw. I was in this state where I was simply aware of where I was and just sticking to the game plan. There were no overwhelming emotions or anything — I wasn’t really nervous. And before the final throw, I could see on the board that I was in the silver medal position. It was possible that someone else could have overtaken me, but that day was really hot and we had some bad wind blowing towards us, so I wasn’t expecting the others to have a super big throw. When I got my chance, I just stuck to my plan — which turned out to be a good idea.

What was it like when you actually won?

At first, it just seemed to me that winning the Olympics was simply another meet in my season — even if it was an important tournament. I don’t think I understood right away what it meant to actually win the Olympics. It actually took a few weeks for me to realise what I had accomplished. It didn’t really strike me during the competition itself. I think that was because I was just exhausted from the athletic performance and from all the emotions I was feeling. Sure, I realised I’d won the Olympics, but it took more time — and possibly returning home to Germany — to understand what a big thing it was to be an Olympic champion.

How did the Olympics change your life?

As soon as you’re an Olympic winner, the power of your voice starts to rise and you can achieve so much more. Your footprint gets bigger, of course, but your obligations grow too. People expect more from you. There are a lot of good things, but challenges come with it. But I wouldn’t trade it for anything. It’s the best thing that ever happened to me.

Where do you keep your Olympic medal?

It’s not mounted on a display or anything because I try to keep my home life somewhat separate from my sports career. At the end of the day, sport is still something like a job. And I also want to get away from my job a bit, even though I love it very much.

My Olympic gold is in my wardrobe with my clothes. I don’t bring it out often — usually only when other people ask if they can take a picture with it. But there are times when I take it out for myself. That’s when I feel I need a bit of motivation. The last time I took it out was two years ago. I was struggling with a lot of issues, with injury and all that, and I wanted to feel some of the old emotions once again.

You’re now a family man and the father of a young boy. Does your Olympic medal mean more to him?

My son is still really young. He doesn’t care much about the medal, but he loves the javelins a lot more. Sometimes he comes with me to training and wants to do everything I do. He wants to lift the bars. He wants to throw the balls. He’s a kid — he just wants to play. He does know the medal is something valuable, but he doesn’t see it as something super holy or precious like adults do. For him, it’s just this heavy golden thing. He’d rather just play.

For my son, I’m just dad — not an Olympic champion. And that’s actually the way I prefer people to deal with me. I don’t want people to think I’m some sort of superhero. I’m just one of the guys who played sports and made it to the top. I think we too often forget all the people along the way who made me that champion — the training group buddies, the coaches, and everyone around me, including my family — they’re important too.

The medal is, of course, nice, but the one thing I do like to have around me are my competition bibs. Those are my only real mementos. I keep all my bibs. Sometimes people ask me for one, and I can’t give it to them because I only have one for each competition, which I keep for myself.

You were at your peak between 2016 and 2019, after which you suffered an injury. How hard was it to come back from that?

If you play at the highest level of sport, you always have to be prepared for something to happen. I was extremely lucky to avoid any major injuries — in what is a very injury-prone event — for nine years in a row. In 2020, I was really pushing myself in training. But when you go for that high-risk approach, you can get high rewards — but there’s also a downside. And for me, it was that back injury. It happens. You need to accept the situation and keep working through it. I needed a lot of patience because it took a long time to recover.

It was strange to have that injury during COVID, which was a very unusual time. The whole world of sport was different. Even though I missed the Olympics, I think it was easier to deal with because competing in those ghost competitions was never that appealing to me. I think even if I had been in good shape, I would have struggled to compete then, because there was no emotion left in the sport. It wasn’t really the sport we love. There was no engagement with fans. Because of that, I was able to concentrate on my rehab and do all the boring stuff without missing the fact that I couldn’t throw a javelin.

Of course, I missed throwing, and it was hard sometimes to watch competitions. But I think it helped that I had already picked the big fruits of being a professional athlete. I had the Olympic and European golds. I’m very happy and satisfied with what I’ve already achieved in sport. So it became a personal challenge — to also accept the bad parts of sport.

Was there ever a moment where you felt like you didn’t need to push yourself and deal with the heartache of missing a second Olympics?

You do have bad days, and then you want to quit. Sometimes you don’t train either. But then, two days later, you start to miss that feeling. I’ve told myself that I will continue to compete as long as I still have that feeling — that I miss training. As long as that stays alive, I’m going to train. I think I’m blessed to be able to do what I do. I know many talented people out there who would love to do this, but they have to go for that nine-to-five job. And I’m lucky enough to do this at a really high level. It’s not like I’m throwing at a city level. I’m still one of the world’s best javelin throwers. I’m throwing above 80 metres. And that’s something I’m pretty happy about.

Were you always interested in being a javelin thrower?

I loved throwing stones from the shore when I was a small kid. I would say I just had this throwing gene. But I was a very skinny, small kid. I wasn’t big and strong like the other boys at the beginning. [He’s currently 6’3’‘] So in the beginning, I tried my luck in the more technical events. I started out as a high jumper and triple jumper.

That made a lot of sense because if you want to stay in the high school sports system in Germany, you need to meet certain standards. And I just wasn’t hitting those standards with the javelin at the time. So I went into high jumping and met the standards there. But on the regional level, I always competed in throwing.

I was okay. Not great, but okay. And my heart was always telling me that throwing was way more fun. So I invested more time in it. And luckily, I had people who supported that. And yeah, then things went really well. I was a decent high jumper. My personal best was 1.96m. I always wanted to get over two metres. I think if I had jumped for one more year, I would have made it. But then it was time to switch to javelin.

I jumped about 14 metres in the triple jump at the U-18 level. People said I could have been a good decathlete, but in Jena — the place where I grew up and did my training — we never had the opportunity to do the pole vault because our gym wasn’t tall enough.

Javelin throwing isn’t a full-time career in Europe. So how do you manage?

I understood very early on that just throwing javelins wasn’t going to make a living for me or my family. So I work with sponsors. I’m an ambassador for different brands. I also do management coaching for the leaders of big businesses. I do this especially in the fall which is the off-season, and when I have a bit more time on my hands.

It’s definitely time-consuming, and I know that if I were in another country, I’d treat my sport a bit differently and allocate my time differently as well. These days I’m usually up by six, sending and replying to emails. I finish that part of my job and then move on to my other job — my javelin training.

I enjoy both sides of my work. I love when big companies call me. I was recently contacted by Allianz and BMW. I enjoyed being able to spread the word about javelin throwing, but they mostly wanted me to talk about elite performance. Most people are happy with being average, but there’s amazing value I can bring from the Olympic side of things into society and business.

What do you enjoy the most about your life right now?

My partner and I started a farm in 2020. We also teach people about vegetables, how to live a natural life and how to nourish the body properly. From time to time, we even host school visits. I enjoy having the freedom to be in the garden at lunchtime and having a healthy family. Apart from this I get the chance to have a good workout every day. All this makes me really happy.

What keeps you motivated right now?

There’s joy in the challenge itself. People outside of sport sometimes ask, “Why do you take on all these burdens? Why do you seek out obstacles?” But as sportspeople, we try to put ourselves in difficult positions. Over time, I think the body starts to crave that challenge — it creates real dopamine, to be honest. Young people get their dopamine from scrolling on phones. I get mine from lifting one kilo more in the gym or throwing the javelin a little bit further.

In what ways do you feel stronger now than you were in, say, 2016 or 2017?

Mentally, I’m stronger now. Of course, the younger athletic body will always be better — more snappy. That’s just nature. But the experience and the mental side of things — no one can take that away from you. Experience only keeps growing.

What do you make of the state of the javelin throw right now? It used to be dominated by European throwers, but now there’s talent from all over the world.

There was always talent — it just needed a spark. Neeraj was exactly that spark that ignited the flame, and now there’s a huge talent pool in India. I think there’s another reason too. Here in Germany, performances in events like the javelin throw aren’t appreciated as much.

In a country like India, your performance gets rewarded. I think that, along with the growing passion for the sport, the time being invested in it, and the sheer mass of people, means there’s going to be a much bigger talent pool in India.

I also have another theory: cricket has played a huge role in the development of javelin talent. In Germany, the sporting culture is built around football. Indian sporting culture revolves more around cricket. And cricket is far more related to javelin than football is. Some people might say the right leg swing is like a football kick, but honestly, football has nothing to do with javelin. So you’ll almost certainly have a bigger talent pool in cricket-playing countries.

Germany had some excellent throwers, but now, apart from Weber, there doesn’t seem to be much talent coming through.

I don’t mind. I love that there’s an international community of throwers. I don’t mind too much where people come from — I just want people to be respectful and enjoy seeing what the human body can achieve in this sport. I’ve had connections to so many countries and training groups. I love seeing them all do well.

German javelin is doing okay, but because we had so much talent coming through at the same time—me, (Andreas) Hofmann, (Johannes) Vetter, and before us Bernhard Seifert — it made it hard for the next generation. We created a big youth gap. We inspired a lot of young throwers by performing well, but we were too good for too long, and the younger guys never really had the chance to step up, and they eventually quit. We’ve seen the exact same thing in Finland. They had a lot of success in javelin, and then there was this huge gap. It’s just the nature of things.

What’s the one thing you’re looking forward to doing in India?

Well, I love international food, so I hope I get to try Indian food. To be honest, I still need to see what’s on the plate! By German standards, we already eat Mediterranean and spicy food at home, including Asian cuisine. So I’m okay with spices — but I’d never go crazy, especially not before a competition.