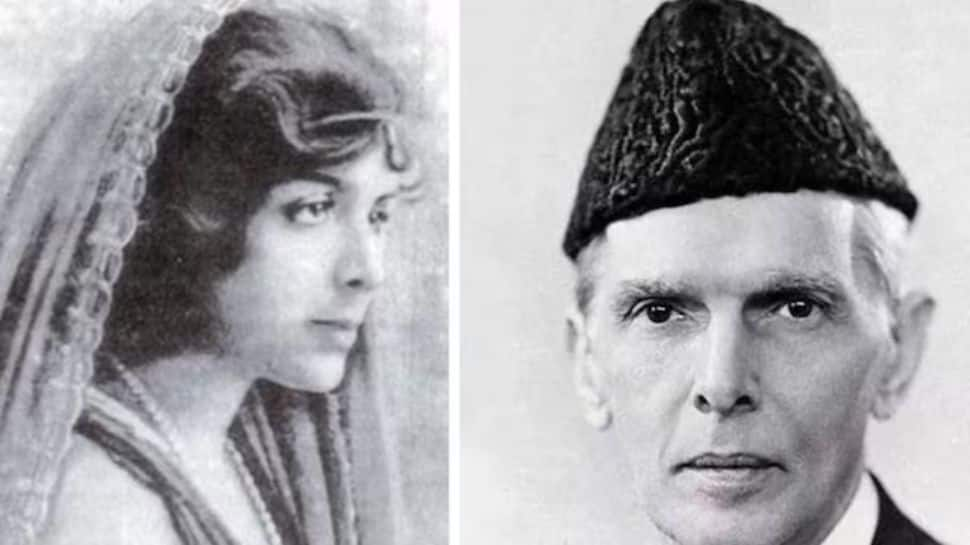

The 16-Year-Old Who Stole Jinnah’s Heart – And Broke It Too | World News

[ad_1]

New Delhi: On an April 1918 morning, Bombay’s elite industrialist Sir Dinshaw Petit sat down for breakfast. A headline jolted his morning calm as he unfolded Bombay Chronicle. The newspaper slipped from his hands.

“Muhammad Ali Jinnah marries Lady Rattanbai Petit.”

The entire city reeled. The man leading India’s charge for constitutional reform had quietly married a 16-year-old Parsi heiress. The whispers had started two years earlier in Darjeeling.

That summer, Sir Dinshaw had invited his lawyer friend, Jinnah, to join the family retreat. Jinnah was 40. Sharp-suited, brilliant and ambitious. Already a storm in the courtrooms of Bombay. Rattanbai – Ruttie – was sixteen, radiant and free-spirited. The kind of beauty that silenced rooms. Within days, something stirred.

Darjeeling’s pine-lined silence, the white peaks and the soft laughter of evenings – they all blurred into a quiet bond. Before the retreat ended, Jinnah had asked Sir Dinshaw what he thought of interfaith marriages.

Sir Dinshaw answered without hesitation, “They help build national unity.”

Jinnah paused. Then calmly said, “I want to marry your daughter.”

The reply was fire. Sir Dinshaw exploded. That very night, he ordered Jinnah to leave. He barred Ruttie from ever meeting him again. Later, he got a court order forbidding any contact between them until she turned eighteen.

But love has its own maps.

Letters crossed secretly. Glances stolen at clubs. Hidden meetings. A silver-haired patriarch stood guard at the gates, but the two hearts kept pace with each other.

When Ruttie turned eighteen, she walked out of her father’s mansion with a single umbrella and a change of clothes. Jinnah was waiting. They went straight to Jamia Masjid. She embraced Islam. The next morning, the nikah was held.

The wedding stunned colonial India. A Muslim barrister and a Parsi heiress. A 24-year age gap. A woman who gave up her religion, her family, her inheritance for love.

Jinnah did not flinch. He did not want a civil marriage. That would cost him his legislative seat. Instead, he chose the Islamic route. Ruttie agreed. He gifted her Rs 1.25 lakh – a fortune in 1918. The wedding meher? A modest Rs 1,001.

For Bombay society, the scandal did not die down. Ruttie became a social icon. Transparent chiffon sarees. Long cigarette holders. Laughter that rang like wind chimes. She was often seen stepping down from a gleaming phaeton, drawing eyes wherever she went.

At parties, she sparred with Viceroys. When one British lord scolded her for greeting him with folded hands instead of a handshake, she smiled. “In India, we greet the British as Indians should.”

Jinnah adored her. Quietly. Stoically. When a Governor’s wife tried to cover Ruttie’s bare shoulders with a shawl, Jinnah stood up. “If my wife is cold, she will ask for it herself.” Then walked out. Never returned to that house again.

But politics waited for no love.

The years passed. Jinnah grew busier. Debates. Speeches. Petitions. Ruttie grew lonelier. Her letters turned heavy. Once, she wrote from a steamer on her way back from France, “I have loved you as no man has ever been loved. Remember me not as the flower you crushed, but as the one you once plucked.”

On February 20, 1929, Ruttie died. She was just 29. Some say illness. Some say too many sleeping pills.

Jinnah was in Delhi. A trunk call came from her father. Ten years of silence broken with a single sentence.

He took the train back to Bombay. At the Khoja cemetery, mourners stood waiting. As her coffin was lowered into the earth, someone handed Jinnah a handful of dirt.

He broke down. Shoulders shaking. Tears flowing.

It was the only time anyone saw Muhammad Ali Jinnah cry in public.

[ad_2]

Source link